The Crisis of Friendship

Modern friendship is different than it once was. How should we think about the role close ties play for a world with less suffering?

If you google “male friendship”, you’ll be met with a long scroll of articles on how lonely the modern man is and how a crisis of male friendship is upon us. I don’t know exactly how the surveys that are informing the data are being run or how reliable the methodology across time can be trusted. But there’s enough of it out there to notice. The one that pops up most is from the Survey Center on American Life. It’s the basis for articles in the New York Times, USA Today, CNN.com and a bunch of other blogs that cite it and run with the angle of male friendship decline as a massive societal problem. Clearly this was something people wanted to write about.

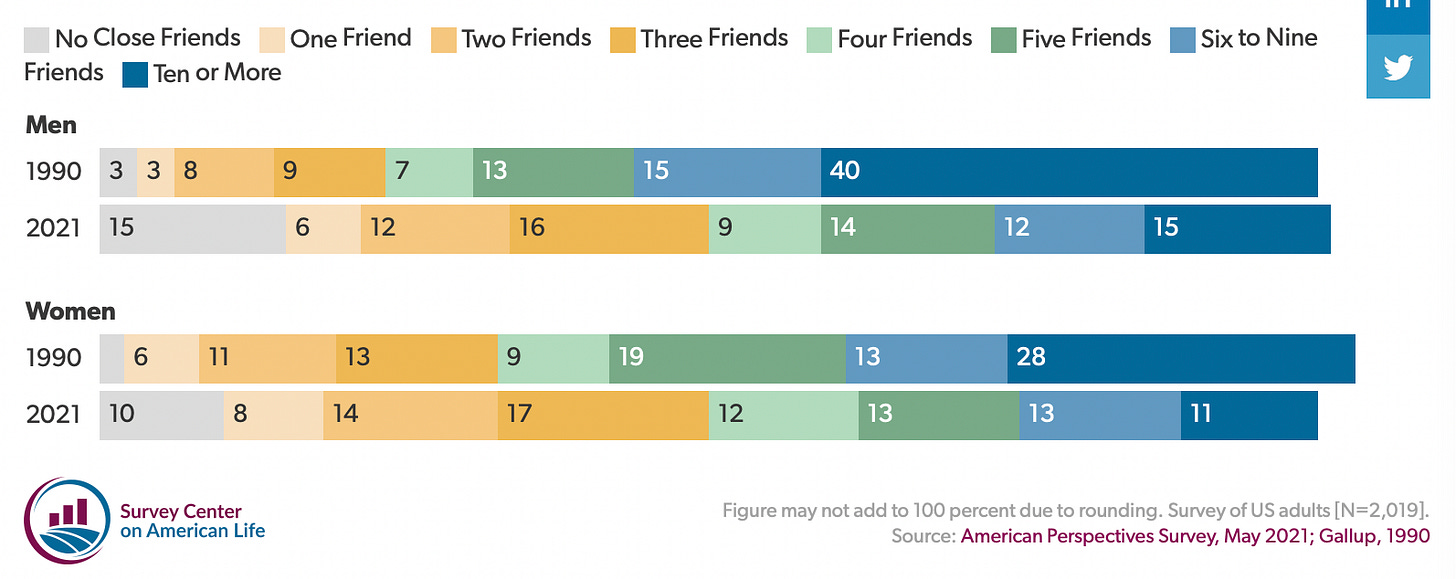

The problem is that the narrative is not supported by the survey that’s cited. Or at least not as a male specific problem. The reduction in friend levels over the last 30 years is pretty consistent across men and women. Moreover, a subset of the survey finds that young women were more likely to lose touch with friends during the most recent years of the pandemic. Yet the headlines about the lonely and unwell men are what they are for the reasons they always are; they sell.

If we’re willing to put down the gendered argument though, we get to a more interesting overall pattern; that over the last 30 years, the amount of men and women who have no close friends at all has increased five fold. The proportional increase is conspicuously identical across both men and women. So it’s probably worth it to dig into a bit of how modern friendship is doing in the world we live in today. And why there are so many lonely people. Or even if having no close friends circa 2022 makes one lonely.

There are a few obvious culprits that contribute to a statistic like one in seven men and one in ten women having no close friends at all when it used to be 1 in 33 and 1 in 50 respectively. Things like the rise of e-commerce, media streaming and internet porn make it far easier to stimulate oneself without ever engaging with another live human. Put differently, there’s a decoupling of loneliness and boredom. I’ve been both lonely and bored in my life at different times. I don’t love either but I’ll take lonely over bored in the modern world. It’s not close. Modern boredom implies being cut off from basic electricity or incapacitated in some way. Lonely and bored together signals suffering. Thankfully, we’re just less bored today. And so it’s reasonable to conclude that having no close friends today is less suffering than it once was. Not un-ironically, I asked my new AI friend ChatGPT what was going on with friendship declines. It returned a reasonably good answer. It’s easy to see why we get along so well.

That one can be entertained to the extent that they are today alone is leading to more prevalent, but more enjoyable, loneliness. That’s pretty clear. The advent of smartphones and now VR devices like the Oculus now even allow us to be alone while with others. When I was a kid the only path to being lonely in a crowd was a cigarette. Still, it’s hard to believe that the driver behind less close friendship is entirely that we’ve lost the need to be entertained by it. When I think about my closest friends, what makes them my friends has nearly nothing to do with their entertainment value. By now we’re a bunch of 40 something working stiffs. We’re not fun. But our friendship is built on caring about each other (masculinity be damned!). And I think that’s where things start to get clearer with the friendship trends. We are establishing less bonds with people outside of our direct families today. The data and the anecdotal evidence match. Some of this is because we spend more time alone because of how much relatively awesomer it is to be alone today than it was in 1990. But that’s not all of it.

When I reflect on the different patterns between myself now, myself 30 years ago and my kids who are where I was 30 years ago today, I can do some comparisons. And if I combine them with the anecdote that we don’t make friends later in life the way they do earlier in life, I’ve got some thoughts around how we spend our time differently now that I think matters a lot. Again, there’s a prevailing opinion that making friends early is a male phenomenon. But there’s not really any literature or data on that. We can, again, put the gendered argument aside as noise.

I fall into the bucket of having at least 10 close friends, which according to the survey is about a third of the size that it was during my parent’s generation. By close I mean people that if we’re in the same town together by chance for a night we have dinner. I know their kids; where they go to school; how their marriage is going and how their job is treating them. Not because I’m nosy. But because I care.

When I tally them up the biggest source of those friendships is classmates from the Naval Academy. My second source is people I served with afterward in the military. Then people I met through my church. And finally, there’s the one friend I’ve known since I was a kid in South Jersey. I’ve known many of them since I was at least as young as 18. The only ones I’ve met after 30 (I’m 45) have come through my church. My wife has similar patterns with the exception that she didn’t serve in the military but instead lives today in the town she grew up and went to college in. She has high school/college friends and people she’s met through our church that round out the full complement of her close friends.

So, it’s true. We do mostly make friends early. But it’s actually not the early part that makes them lifelong friends. If it were, our closest friends would all be the people we sat next to in kindergarten. What matters is that when we’re young we have a specific type of experience with others. And that experience becomes less and less common as we get older. Childhood is a shared journey. It has a common origin and a common goal. There’s ample and consistent time spent with others on that journey that we are not inherently competing with. And there are forces (good and bad) that act consistently upon as we progress. We establish tight bonds with those sorts of experiences. The place to look to see why close friendship levels are decreasing is why we don’t have as many shared journeys with others as we once did.

There are some pretty telling patterns in my life. I’ve been out of the military full time for 11 years. I’ve worked at the same major tech firm for all of those 11 years. Of the close friends I counted as part of this essay, not a single one comes from my current job. And it’s fair to say that most of the people I work with would tell you the same. We’ve got plenty of mentors and acquaintances and people we enjoy spending time with. We’ve got friends. But not the sorts of closely held friends that I categorize in that group of close. Why? Because we’re not on the same hero’s journey together…no matter what our employee engagement team says.

When I tell people I’ve worked at the same tech firm for 11 years they aren’t surprised. They’re shocked. My tenure at one firm in big tech is an outlier. Moreover, in March of 2020, on a week’s notice, the entire company went home and worked from there indefinitely. Many are still there. If you tried a similar thing in 1990 when legacy friendship data came from, it would have been impossible. We didn’t have technology or an organizational structure that could be so easily decoupled from location. But today, we live in a different world. It’s a world where the massive body pools of people doing the exact same job, the ones on a shared journey together, have been automated. Our requirements to be face to face to communicate are nonexistent. And if there is someone exactly like us doing the same thing as us, we’re competing with each other. That’s not a shared journey. So that’s not where we make bonds.

This is not a knock on where I work by the way. I love it there. They’ll have to drag me out kicking and screaming one day.

In contrast, I’ve established multiple close friendships with people at my church that I started attending at the same time that I started my job. My church disclaimer is that I grew up in the Catholic Church and went to Catholic school but drifted away in adulthood. I came back to a nondenominational church in our community after the crisis of my son’s severe autism diagnosis. And what that experience has taught me is that good churches (of any faith) are really, really good at putting people on a shared journey. When someone in your small group of special needs parents at your church asks you to pray for them to have the strength to make it through the first night that they’ve put their special needs child in a home, you’ve joined their journey in a powerful way. And when you do it week in and week out for years, you establish permanent bonds. Beyond the subgroups as well, we’re all on the shared journey of growing in our faith.

Not surprisingly, church attendance has taken a significant dive in the last 30 years. And with it certainly has some of the opportunity to bond with people who may become close friends.

As for the rest of where my friends came from, it’s the military or some version of it at Annapolis. Once, we were all just coals drawing heat from the same fire of service. There is no better creator of a shared journey than the prospect of war. Military spouses are on that same journey. Cops share a journey. Firemen…nurses. They start the same way. They do the same jobs with the same purpose. And they bond. Their primary work activities depend on each other in ways far fewer jobs do today. They cover for each other.

One test to see if your job fosters close friendships is to ask yourself when the last time you “covered for someone” at work was. And by covered I don’t mean went to a meeting your boss or subordinate couldn’t go to. I mean did another person’s task because it was a normal part of a rotation. There are still many jobs where this is common. But they are more transient than they once were and there are fewer of them. The work we do now is much more compartmentalized. And so there’s less opportunities for the bonds of close friendship.

The data support this. A recent Gallup report on the millennial generation reveals that 21% of millennials say they've changed jobs within the past year, which is more than three times the number of non-millennials who report the same.

So it’s clear. We spend more time alone. The time we do spend with others at work or in other consistent activities is different than it once was. And there’s one other thing that I think matters. Childhood and teenage years are massively different than they once were.

Both the data and common observation/opinion show that kids today have very little unstructured time relative to previous generations. It’s a trend that’s been a few decades in the making and the drivers are probably a source for a different essay. But what’s clear is that the journey for kids is still a thing. In fact it’s almost certainly more complicated and arduous than it once was. It’s a hero’s journey now. But it’s so crammed with supervision that the bonding time required to make it a shared journey may be gone. And so the bonds and friendship of young childhood have headwinds.

If you’re not sure if this is true, check out the data behind how teenagers are doing these days. They have less sex and do less drugs (including drinking) today than my generation and my parent’s generation. This is a reversal of a trend millennia in the making. If you match this with the correlated decrease in church attendance and a reasonable assumption that we’re not particularly more moral than we were 30 years ago, then the strongest conclusion we can draw is that kids are just spending less unsupervised time together physically. And to be clear, I’m not advocating for more underage drinking and sex. As a parent, I’m excited that it’s something I need to worry less about now than my parents might have.

Kids are also reporting more mental health issues today. I’m less bullish on the relationship to a lack of partying to an increase in mental health issues than I am on appreciating the positive change from a reality that 16 year old me wouldn’t have even known where to go to tell anyone I was depressed. Besides my friends of course.

Once we break down the modern behavioral patterns in the world today, it’s not really that hard to find out why we’ve got less friends today than we did 30 years ago. We spend more time alone. We go to church less. We work differently. And our kids don’t hang out that much any more. These are likely durable shifts that, at a minimum, won’t reverse in the short term. I think the next most interesting question is related to how we should feel about it. Is it a crisis that we have less friends today than 30 years ago?

I’m not sure it is. Here’s a couple of things to think about:

The first is one I keep close to me when I think of any trends that the world tries to sell me on. It’s that many of us that grew up in the 80s and 90s have normalized it. But it was a weird time. It was weird in that it was stable, prosperous and included adults that came of age after the cultural revolution of the 60s, which is a unique convergence. Many things that are compared to the 1990s today will seem like they’re traveling in the wrong direction. I don’t know if 1990s friendship in the literal era of Friends is a great comparison. It’s entirely possible that we’re not in fact unraveling as a society and mass producing psychopaths. But instead normalizing. How many close friends did a 19th century agricultural worker have…?

The second is to understand that there’s something Malthusian about the mix of technology, vice and social interaction that is different across generations. Today, I’m more connected with my four roommates from Annapolis than I have been since we lived together because we have a group text that gets daily engagement. That means I talk to my college roommates every day in a way that wasn’t possible 30 years ago. It’s possible (likely?) that the optimal level of close friendships changes relatively with the ability to engage with people. It’s possible the right amount of friends in 2023 is not what it was in 1990.

The last is that there is now a distinctly modern sort of close’ish friendship that simply didn’t exist before. There are people that I have met through social media channels that may not be as close as my closest friendships. But they’re closer than you think; specifically in ways where I know that if I asked them for help, they would help. There’s something to the weird mix of anonymity and transparency that comes from a close Twitter mutual that is hard to capture in the context of normal friendship. You have the ability to assess their aspirational versions of themselves, have a reasonable expectation of discretion in direct communications and the ability to out them to your shared community if they turn out to be horrible humans. And you see them (in some form) daily. There’s more trust than you’d think. And it’s entirely new. I don’t know how exactly it eats into the aggregate demand for close friendship. But I think it’s at least a little. And I’m less likely to call it a negative trend than many others. Trading in all intimate friendships for Twitter mutuals is almost certainly a recipe for worse outcomes. But ignoring the impact also misses some of the broader points.

The world is different today than it was yesterday. And tomorrow it will be different again. As times change, so does the nature of friendship. As crises go, this one seems early and we at least have to understand what it means to be alone in 2023 before we declare that we’re on our way to ruin. That said, I do think that the growth of more people with no close ties at all combined with decrease in marriage rates and parenthood and increases in marriage age signals some increase in loneliness and suffering and a problem to be solved. But it’s also worth understanding how bonds are made differently across different mediums today. It’s hard to imagine a world where people had more opportunities to create close bonds wasn’t a shift towards more positive. And in that a better and more stable future. I’m not exactly sure how to think about friendship in the grand scheme of things that compete for 21st human attention. But it’s almost certainly not more important. Maybe less?

There is a lot to unpack here, and I have reread a few times. Do you think that being in the military and part of a church has allowed the opportunity for you to better understand what it means to have close friends? Do you think Smartphones impact teens having a chance to make friends the way we did in high school/college, or are you pondering that there is just a new normal for the definition of friends in the teen world?

There are a lot of transplants in the engineering firm I manage, and a lot of people in my brother's tech world who were never in the military and don't go to a spiritual center. It does seem that unless they have some type of sporting or gaming community, or a bar they frequent (which brings its own set of issues), the young people, and older people with no previous ties to the area, have a harder time making friends.