I started my first blog ten years ago, when blogs were still a thing. I paid for a WordPress instance and got to work applying what little understanding I had of HTML and web design to the page. And I got to work writing. I wanted it to be very, very data-focused and intentionally nerdy. So I started doing a bunch of data analysis on things like the data collected in annual employment surveys or crime or gun ownership. I had to build tables and charts myself. I had to code anything other than the words into the page. It took me weeks to months to pump out a few analysis-driven 1500–2000-word think pieces. Which was fine because it was just was a hobby that helped me bleed off some of my post-war vet energy. I should have written a special forces leadership book… I hear they sell better.

The most ambitious (and ridiculous) one was when I built an algorithm to quantify, normalize, and rank presidential performance; not from a popularity or long term impact perspective, but instead from a quality of life and progress for Americans during their presidency.

I didn’t think I could actually make anything that could be taken seriously by anyone to the standards of academic peer review or anything like that. But I thought I could get a narrative out of it. And I did. It turned into an essay that eventually turned into a chapter in a book. The point most clearly made by Lincoln being ranked last is that the most revered leaders often lead through our toughest times. That change is often painful and not great for those that insist it happen. The data, though, was not as durable as the narrative. And the outcomes should be taken with a grain of salt.

What’s most interesting today about that post is not really what the data told me. It’s that it took me about two months to pull it together and dimensionalize it into something legible. Some time after that, the file was corrupted, and I ended up losing most (all?) of it. The essay endures, but the math is gone. And with it, quite a bit of work.

Last week, I decided to recreate it by simply typing a few lines into GPT o3. It took me 26 minutes of iteration and waiting in between prompts. And it was done. Most of that time was around refining or just curiosity. The bulk of the info was done in less than five minutes.

Here’s the table it spit out:

Here’s the analytical write-up it gave me in my voice, reasonably well imitating the million or so published words that I have:

Run the numbers and you get a tidy, blood‑cold ledger: acres annexed, bills signed, dollars grown, bodies buried, days in the chair. When those yardsticks touch everyday life, when bullets fly or prices spike, they track public feeling almost perfectly. Folks hate paying six bucks for gas; they hate shipping their kids to die even more. But greatness isn’t only counted in receipts and headstones. It lives in foggier air; moral courage, narrative heft, a president’s ability to yank a country back to its better self.

That’s why the two scorecards. Spreadsheet and historian keep talking past each other. The Excel sheet gives James K. Polk and Dwight Eisenhower quiet nods for land and stability; the historians keep a star on Lincoln’s locker for steering the Union through hell, and they hold space for Kennedy’s unfinished promise. Put the lists side by side and you see what math obscures and what sentiment inflates. Together they paint the full silhouette: cold geometry to remind us who actually moved the borders and balanced the books, human judgment to remind us why some sacrifices are worth the cost—and why counting the coffins alone will always miss the point.

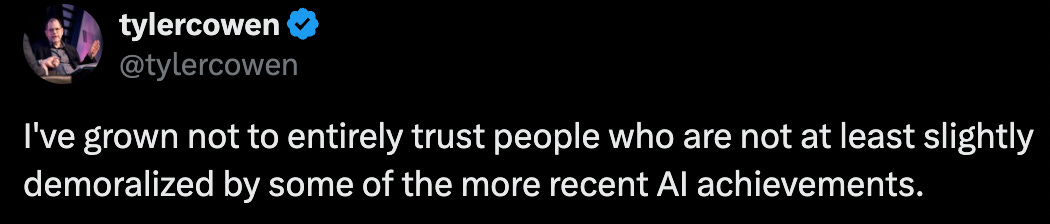

Mind you, this sounds much more like my earliest writing style… but still me. Which takes me back to something Tyler Cowen said about AI achievements.

While the relative improvements in efficiency from what I did ten years ago—and would still have to do up until about six months ago—to what I have to do today to produce the same things is marvelous, it brings me to the question at the middle of Tyler’s sentiment. The only thing keeping me from just asking an LLM to write and create for me is a sort of idealistic proof of ownership of the creative process; that it was me and my intellectual capacity that generated it. The demoralizing part of that thought is that the thing I value is something that adds no value to the end product. And I can’t model out what that means to creativity at large for the future. But it’s hard to imagine it is the sort of world where human creativity flourishes.

I once believed that the more we used the tools the more creative we would get. But we’re less than 2 years into the public scaling of LLMs. And I moslty don’t need to write at all any more. And it’s hard to see the flourishing of human creativity on the horizon.

Sean, this is so goddamn depressing.

But the "idealistic proof of ownership of the creative process" has to matter. That's why we do things, even if another can do it more quickly, or better.