Childhood's End

What We Must Become

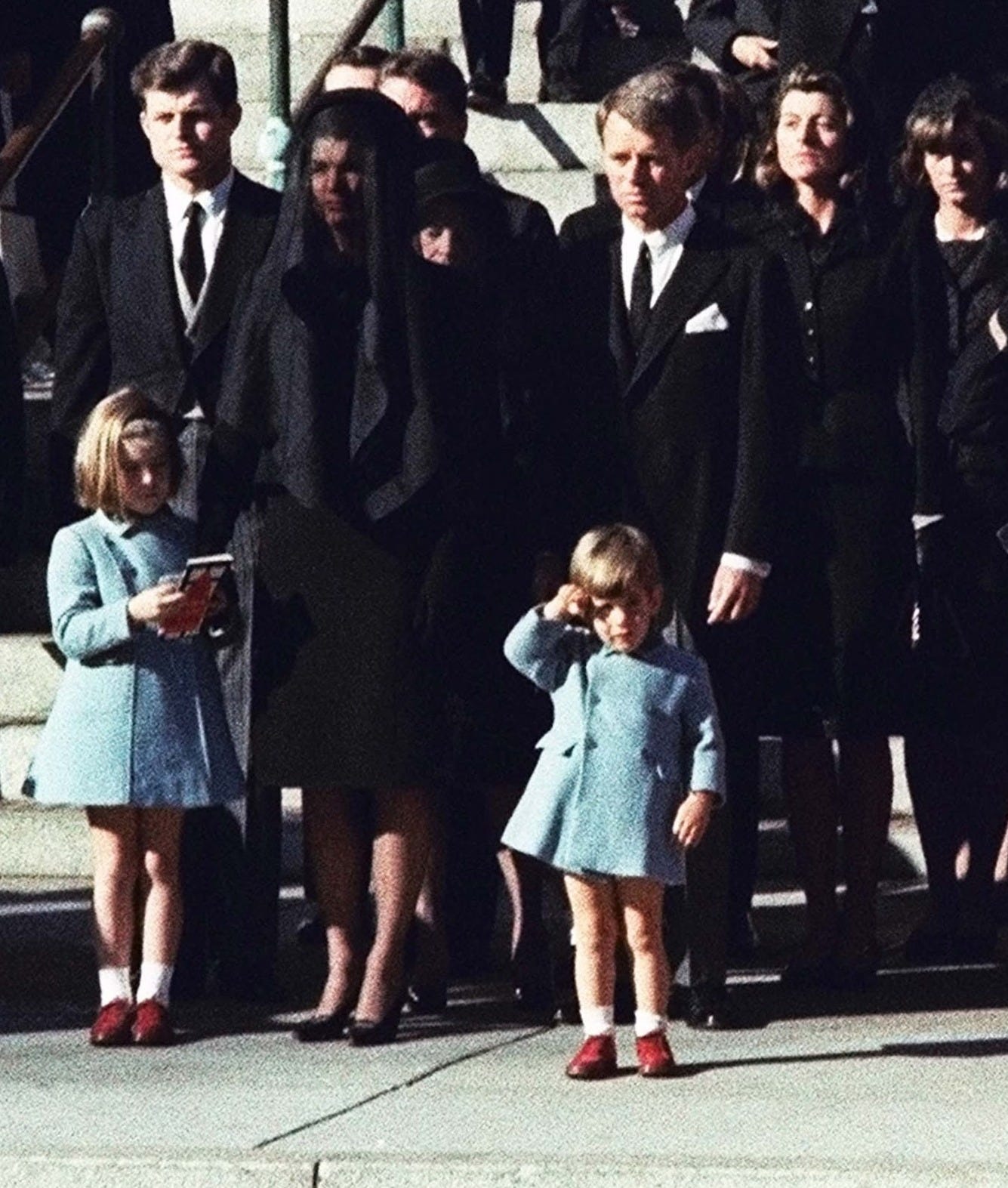

There’s a photograph that haunts us. John F. Kennedy Jr., three years old, saluting his father’s casket. He stands in his short coat. His small hand raised in perfect military form. He performs a ritual he cannot possibly understand. He knows only that something has ended. That the world has changed. He lacks the vocabulary to name what has been lost. That image, innocence confronting rupture, a child suddenly forced into knowledge, captures something essential about the moment we now inhabit as a nation.

We are that boy now. Standing at attention before something we only dimly comprehend. The living generations of Americans have reached the end of our own childhood; the conclusion of an era that began in the turbulent years of the 1960s, when the civil rights movement and the cultural revolution that accompanied it created a new American identity, one built on the promise that progress was not merely possible but inevitable, that the arc of history bent inexorably toward justice. For sixty years we lived inside that assumption, sheltered by the belief that the moral victories of that decade had set us on an irreversible course. That childhood is over.

Bruno Macaes observed something crucial about postwar Europe. It built itself around a negative principle. The Holocaust must never happen again. Not what Europe was. What it would refuse to become. The entire architecture of the European Union, the elaborate systems of international cooperation, the careful monitoring of nationalist sentiment, all of it built on the foundation of absence, on the determination to prevent a return to a specific horror.

There is power in such a commitment. But also emptiness.

Now Europe faces enemies at the gate. A resurgent Russia. The pressures of mass migration. The fracturing of the postwar order. And Europe finds itself paralyzed by its own construction. When your identity consists of what you will not do, what happens when circumstances demand affirmative action? When not being the past proves insufficient to meet present dangers? The European crisis reveals the fundamental weakness of building a civilization on negation: it provides no reserves of conviction when conviction is required, no sense of what is worth defending beyond the abstract commitment to avoid repeating history.

America followed the same path. We knew what we would not be again. Not the nation of segregation. Not separate water fountains and back of the bus humiliation. Not lynchings and legal discrimination. This knowledge was crucial. Hard won. Purchased with blood in Birmingham and Selma, with the assassination of leaders and the courage of ordinary people who risked everything to demand their rights.

But somewhere in the translation of civil rights victories into ongoing political momentum, the positive vision became obscured. What emerged instead was a narrative that defined America primarily through its sins. The message became not “this is what America can be” but “this is what America has been and must never be again.” Where was the articulation of what America was, in its fullest sense? What affirmative identity could citizens embrace beyond the commitment to avoid past evils?

Most Americans (or people) struggle with an identity built on inherited guilt. They are rarely satisfied with being told that their national story is fundamentally one of oppression. That racism is not a historical wrong to be overcome but a permanent, systemic condition embedded in the nation’s DNA. Not because Americans are incapable of confronting hard truths; the civil rights movement itself proves otherwise. But because an identity built solely on negation and guilt provides no path forward, no way to participate meaningfully in building something worthy of devotion.

Into this vacuum came MAGA. Make America great again. Whatever else one might say about this slogan, it offered something the progressive narrative had ceased to provide: an affirmative vision. A sense of what America could be again rather than merely what it should avoid becoming. It spoke to people hungry for a story about their country that included them as protagonists rather than villains. The appeal was not about policy. It was about narrative. About being offered an identity that felt like an invitation rather than an indictment.

Trump’s political success marks the end of an era. For decades, progressive causes benefited from momentum protection; the sense that they were riding the inevitable wave of history. That to oppose them was to be on the wrong side of progress itself. Dissent could be dismissed not through argument but through categorization. To question prevailing progressive orthodoxies was to mark oneself as regressive. As someone who had learned nothing from the moral lessons of the 1960s.

That protection has expired. Trump’s presidency served as the angel of death for the assumption that progressive momentum was self sustaining. The childhood of our post civil rights world has ended, whether we were preparef for it nor not. What comes next will require something different: The hard work of persuasion. The construction of arguments that convince rather than coerce. The articulation of a positive vision that can compete in the marketplace of ideas without relying on the rhetorical (even if accurate) shortcut of labeling opponents as bigots.

But we also have to confront a darker possibility. The void left by the collapse of inevitable progress creates space not only for new positive visions but for something more dangerous. Nihilism. When no one believes in anything, neither in the progressive narrative of inevitable advancement nor in any competing vision of what America should be, they may come to believe in the only thing that remains viscerally real: chaos and pain.

The risk of domestic political violence grows not from conviction but from its absence. From the sense that if nothing means anything, then destruction becomes its own purpose. The only authentic act left available. We’ve already seen glimpses of it. Not the violence of ideological commitment but the violence of those who have concluded that the system itself is empty theater. That breaking things is the only honest response to a world of manufactured meanings.

This is the gravest danger of the transition we’re deperately trying to navigate. That in the space between the old childhood certainties and whatever maturity might replace them, we will see a proliferation of violence born not from belief but from the absence of it. From citizens who have given up on the possibility that anything might be worth building and have embraced destruction as the only remaining form of authenticity.

Yet this transition, painful and dangerous as it may be, offers the possibility of genuine progress. If we can navigate it. If we can resist the pull of nihilism. If we refuse the backsliding into the worst of our history. Real advancement cannot rest on protected status or on the assumption that history moves in only one direction. It requires engagement with reality. With the actual views and concerns of citizens. With the necessity of building coalitions through persuasion rather than presumption. When progressives can no longer rely on the inherent rightness of our position as self evident. When we must make our case rather than assert it, the quality of thought and argument can improve.

The test now is whether we can find leaders capable of guiding us through this new landscape. Leaders who can articulate a vision of America that includes both an honest reckoning with historical injustice and an affirmative sense of national purpose. Who can inspire without manipulating. Who can acknowledge complexity without surrendering to cynicism. We need voices that can speak to what America is and can become, not merely what it has been and must avoid repeating. Most critically, we need leaders who can offer American something to believe in before the belief in nothing metastasizes into something far worse.

That photograph of the small boy saluting reminds us that endings come whether we are prepared for them or not. That history moves forward regardless of whether we understand what we are losing. But it also reminds us that life continues after loss. That the child in the photograph grows into his own man. That new chapters begin even as old ones close.

Our task now is to write that next chapter. With clearer eyes and steadier hands than we have shown in recent years. To move beyond the childhood of our post civil rights era and into a maturity that can sustain the work of building a more perfect union not through assumption but through achievement. And that can offer a compelling enough vision to pull us back from the abyss of meaninglessness that threatens to swallow us whole.

What message is going to drive us into the future? Who are we going to be?

Thanks for this framing about positive visioning vs avoiding negatives. It makes me think about the lifecycle of social movements. The civil rights movement started as activism, then moved into institutional reforms of the Civil Rights Era, then became more widely accepted in a consolidation phase. In the past decade, it went activist again and too far left of the mainstream, provoking a backlash. Does a movement feel like it dies when it’s in the consolidation phase and the activists get restless?